Let me tell you about my boots.

My boots are Storm Officer’s boots: made of black leather, they are full length with red trim, and they match my uniform—that of a Storm Lieutenant (although I am actually a Storm Captain) in service of the thalassocratic city-state of Limsa Lominsa. I have a matching bicorner hat, but I seldom wear it.

Of course, that’s only what my boots appear to be because they’ve been glamoured (given the appearance of another item) in order to look that way. My boots are, in fact, Augmented Credendum Sollerets of Casting—the best boots currently available to Black Mages ahead of the 28 June release of Dawntrail, the latest expansion for Final Fantasy XIV. They weren’t particularly difficult to get.

That’s enough about boots for now.

Final Fantasy XIV was released on 30 September 2010. Very long-term listeners and readers will recall that I played it with some of the then-staff of this website. Despite being one of the clunkiest, weirdest MMOs ever made, I did not dislike it. In this impression, I was mostly alone, and the game was taken offline for years. A parade of various Square Enix executives bowed deeply and apologised profusely, swearing to do whatever it took, at whatever cost, in order to regain the trust of dissatisfied gamers following the ‘damage’ to the ‘brand’. The director of Final Fantasy XIV, Hiromichi Tanaka—who had joined Square alongside his friend Hironobu Sakaguchi, and who had built an illustrious career by doing the game design for Final Fantasy and its sequels before producing Secret of Mana and XenoGears and directing Final Fantasy XI—was internally ‘resassigned’ to an empty desk. Two years later, he resigned for ‘health reasons’. Since then, he’s been involved with a couple of mobile titles.

The lesson was not learnt. After the dismal production of Final Fantasy XV saw its director, Hajime Tabata, similarly ‘reassigned’, he too tendered his own resignation. Since then, he’s been involved with the development of one mobile title. Naoki “Yoshi-P” Yoshida, the director of the latest flop—Final Fantasy XVI—was likely saved from a similar fate only because he is the current director of Final Fantasy XIV. The MMO may have claimed one director, but it has saved Yoshi-P, largely by virtue of his leading the recovery that took XIV from being the most notorious disaster in the company’s history to being its only outstanding success in the ‘main series’ Final Fantasy games since Final Fantasy XII, which released all the way back in the PlayStation 2 era.

In Final Fantasy XIV, appearances are everything.

Players are delighted into staying subscribed by the prospect of being able to dress up their characters in all manner of attractive styles, complete with portraits and profile frames designed to accent the focus on fashion. My aforementioned boots (and the glamour system) are just one part of this quite massive aspect of game design. Not only are characters customisable—and on track to become moreso in Dawntrail—but so are their chocobo companions, which can be dressed up and dyed into an almost numberless array of combinations.

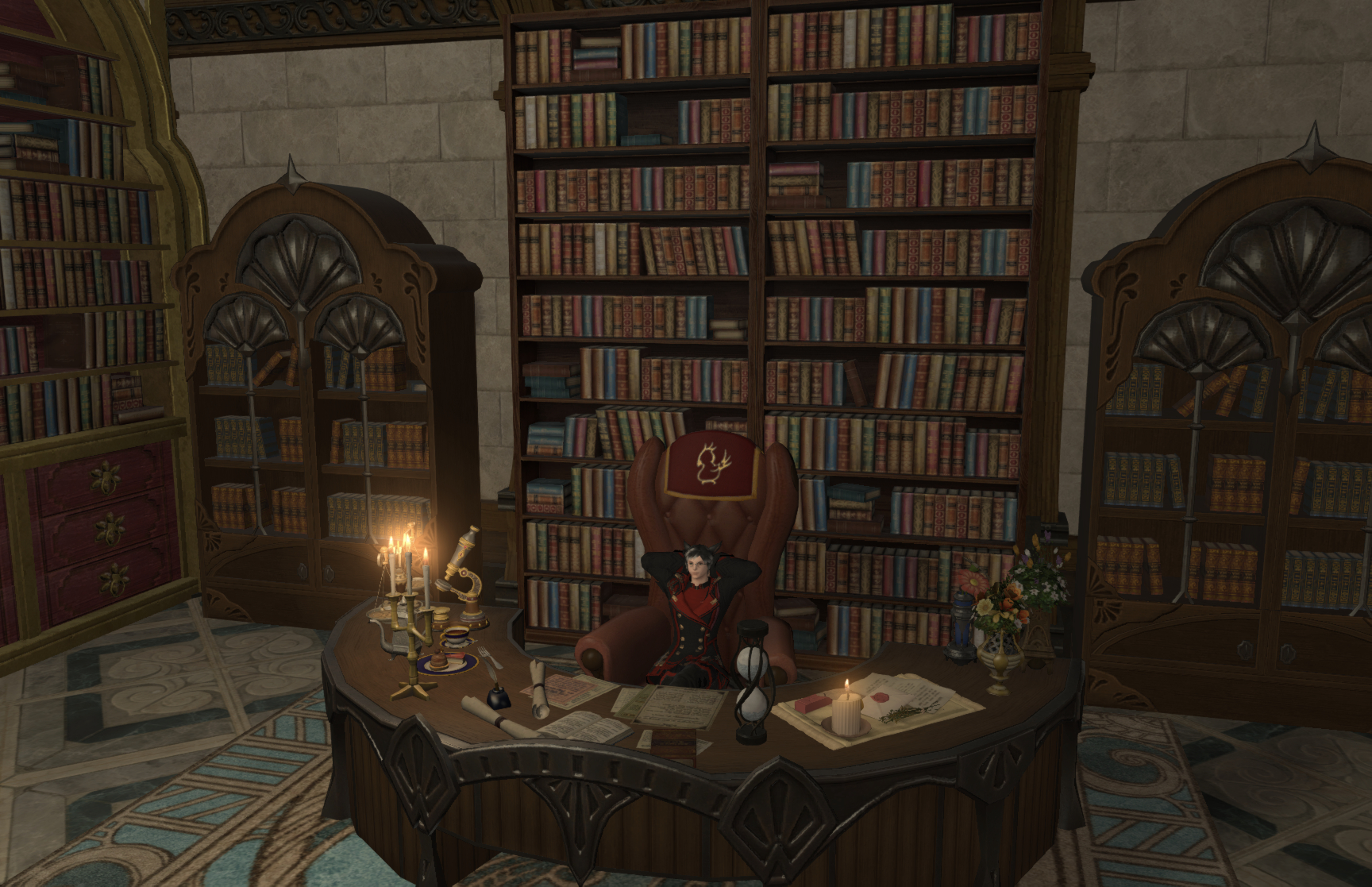

The customisation doesn’t extend only to characters: player and free company housing can be extensively, near-infinitely, customised. Millions of gil can be spent on designing the boldest of bold houses. Countless thousands of players aspire to those lofty heights, while a few other players choose to live in empty rooms without so much as a stick of furniture. Pictures, furnishings, rugs, walls, music, lighting, and more are all available for individual customisation. The Starlight Megaphone free company boasts modest but attractive outdoor gardens and seating, whilst indoors there are comfortable couches and chairs, a cozy library, and a bamboo-dressed bathing room.

Yoshi-P brought in standard MMO mechanics: skills that could be assigned to action bars and then executed, along with player guilds (known as free companies), auction houses (known as market boards), chat channels (known as linkshells), and a bevy of quests, dungeons, raids, and boss fights. Both the high fantasy setting and style of presentation of Final Fantasy XII were energetically copied, to massive fan approbation. And, in the years since, Yoshi-P has rewritten the Ivalice Alliance setting, turning it into his own personal XIV playground, and situating his game in the reimagined universe. Players have responded enthusiastically, as Final Fantasy XIV‘s playerbase continues to grow with no signs of slowing.

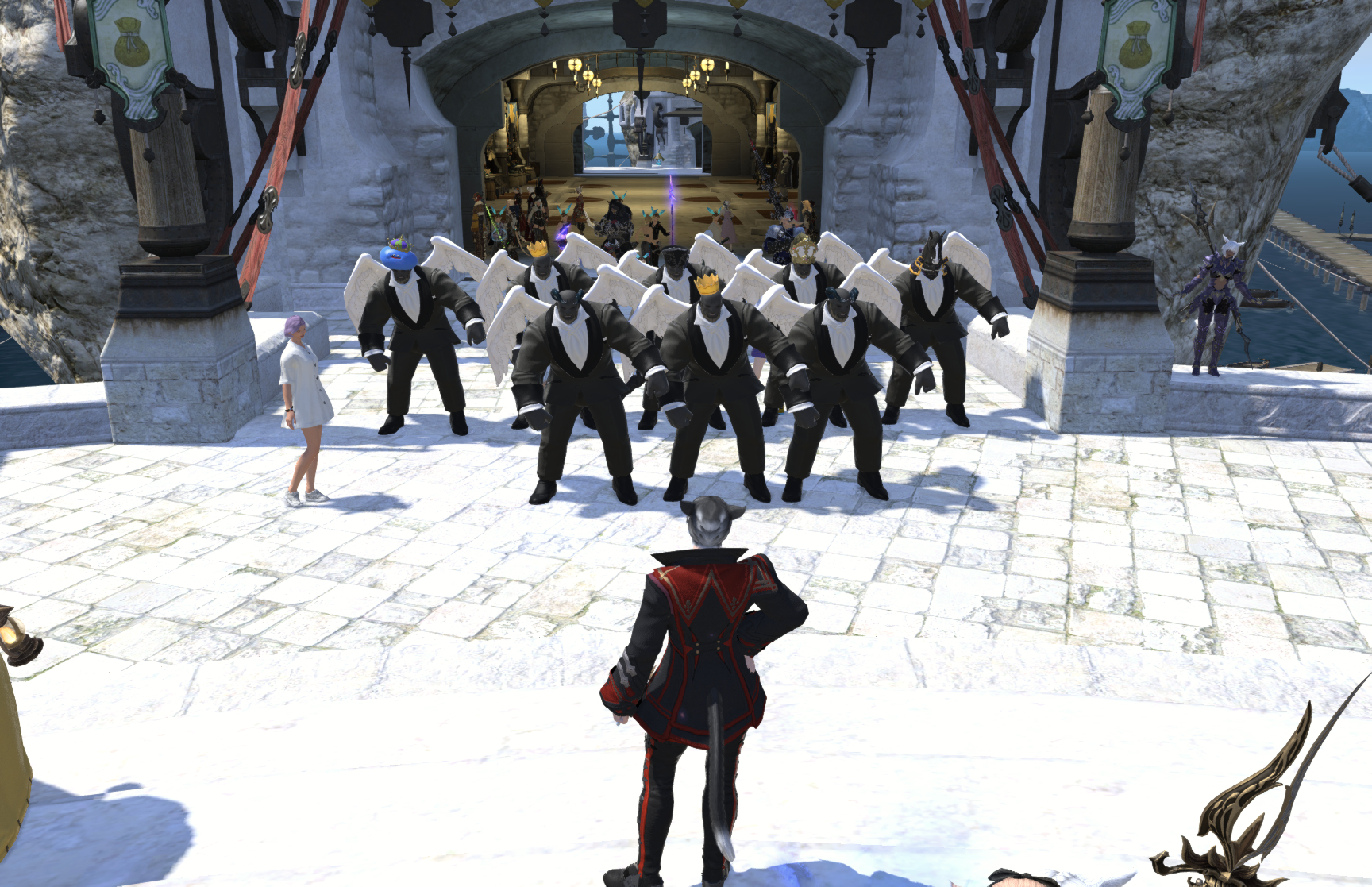

As Activision Blizzard increasingly became more Activision and less Blizzard, players of the world’s biggest MMO—World of Warcraft—found themselves looking for a new home, where they could once again feel like they were in a vibrant community at the forefront of MMO design. They turned to Final Fantasy XIV, making it the main competitor to ActiBlizzard’s offering. Then, when a global pandemic occurred, and lockdowns were implemented which forced many people indoors, MMOs got another huge boost. Final Fantasy XIV became so popular that the game was withdrawn from sale, when the server space available simply couldn’t cope with the influx of new players. With new customers also came a flood of bots eager to scam the new arrivals out of their credit card numbers and game login details, with promises of in-game currency. For years now, the game’s development team has been locked in an intractable battle with these bot farms: thousands are banned, and the farms retaliate with DDoS attacks before creating new accounts. Often, the bots are set up to dance in unison in town, almost as if to taunt the players and developers alike.

Move over, Super Mario Sunshine.

Final Fantasy XIV is filled with side-content, sometimes in the form of completely, fully-realised games that are nested inside of it: Triple Triad, Chocobo Racing, Minion Battling, Eureka, Bozjan, and more—all of these could constitute a game in their own right, given the degree to which they have been realised.

But there is also platforming, in the form of the ‘Sightseeing Log’, which requires characters to stand in a particular place (sometimes at a particular time and during a particular weather effect), and then use a specific emote (usually /lookout). Doing so will complete an entry for that particular vista. Some of the entries—such as that for the Kugane tower and the lamppost beneath it—have been the subject of multi-hour essays. Durga has abandoned his efforts, and I stuck a landing at 0230 in the morning after hours of work, in an accomplishment that ranks amongst the hardest platforming challenges I’ve ever encountered.

It’s not all dancing bots and player customisation. Some long quest chains include many hours of cutscenes, and some in chunks so long that warnings are attached. Other quest chains involve running back and forth talking to party A, then party B, then party A, then party B, then party A, then party B, until the absurdity of it transforms the experience into farce. The game’s systems are so numerous and so arcane that it cannot be played successfully without recourse to a Wiki, although the system overall is still more welcoming than Final Fantasy XI, which made no concessions whatsoever to approachability or even intelligibility.

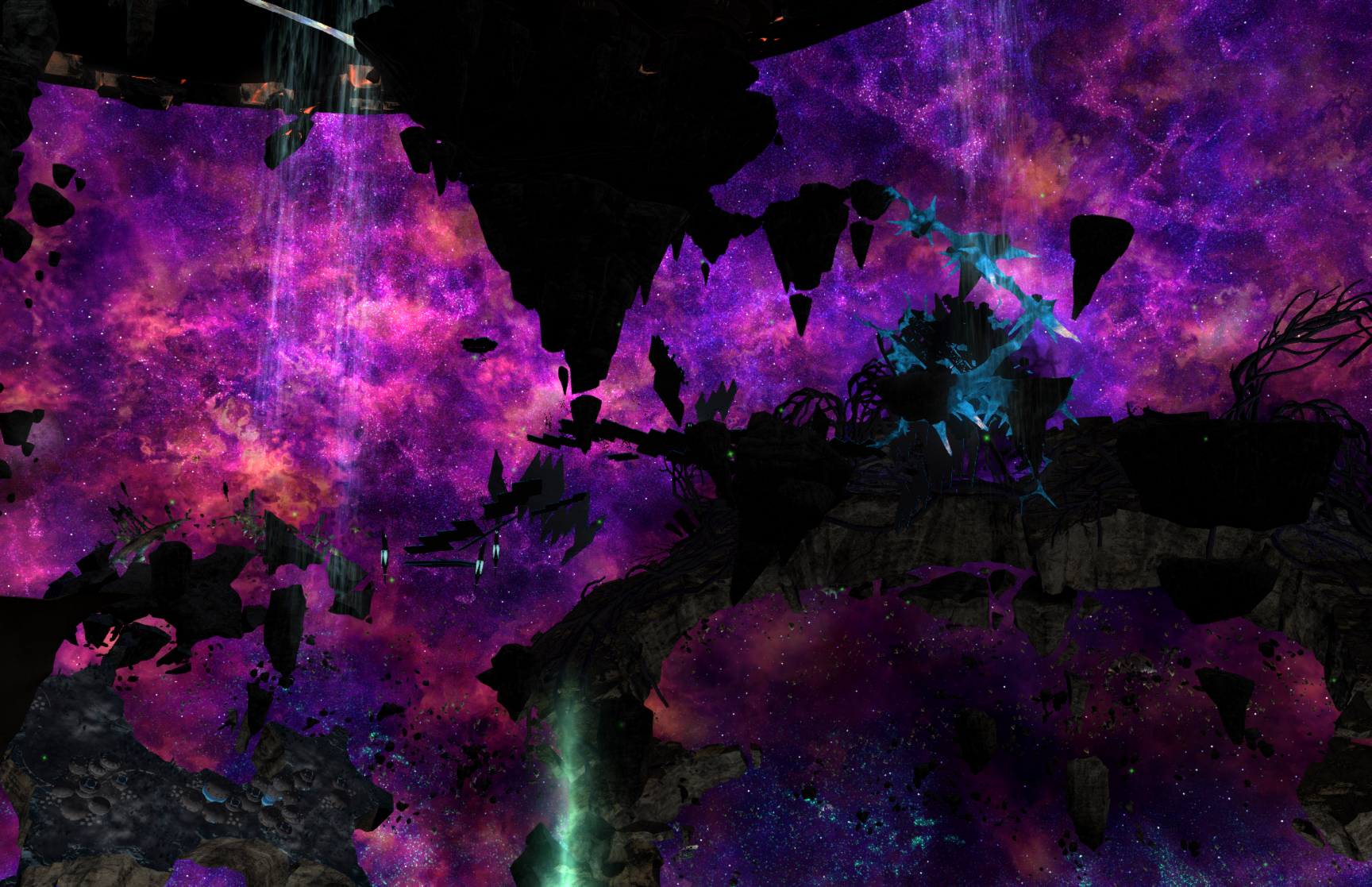

But navigating the confusion and obscurity is worthwhile, because it forces one to realise how confusing and obscure reality itself is. Our own lives are full of an infinity of systems so complex and arcane that they would stagger a visitor from another realm. It is only our lifelong immersion in those systems that makes them seem anything like approachable—and, as anyone who has dealt with bureaucracy knows, even long familiarity with the systems of our reality isn’t always enough to make it endurable. Push through the complexity and the challenge with the Wiki to hand, and suddenly the mists part to reveal an immersive world with something for everyone, from the sunny seaside of Limsa Lominsa, to the frozen wastes of Garlemald, and then to the moon and beyond even to the stars, and the Cafe at the End of the Universe.

Such a creation defies review. It seems impossible for anyone to review something as copious as a world. For to realise even a failed world is to accomplish more than most; and to realise something as successful as Final Fantasy XIV seems to merit unstinting praise, flaws notwithstanding.

When I log out for the last time, whenever that day comes, I might regret having spent so much time in Final Fantasy XIV—more than two thousand hours, at this point. But as with FFXI and WoW, I have memories that feel like memories of a real, living place—far more tangible than any I have from Borderlands 2 or Diablo or StarCraft, all games in which I have spent considerably more time. I have lived in Eorzea the way that I lived on Azeroth and Vana’diel, and that experience—good and bad alike—is absolutely worth the price of admission.

See you in the game.

Game Information

Title: Final Fantasy XIV

Genre: Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game

Developer: Square Enix

Publisher: Square Enix

Platform Reviewed: PlayStation 5

Release Date: 30 September 2010 (Windows), relaunched 27 August 2013 (PS3/Windows)

I just want to say that I took all of the pictures used in this post (on the PC, not the PS5). Those really are images of our FC estate and my room in the estate house.

In case anyone wonders where the orange chair are now located, they’re in the basement of our FC estate so that I can be kept to work manufacturing airship parts.